Published on Apr 14, 2017

Topic: Technology

File systems are organized hierarchically. This makes sense, and is somewhat intuitive to use. This is how your computer works. Everything is organized relative to the “root directory” (/ on Mac/Linux/BSD, C:\ on Windows). Every document, every executable, every system file is organized somewhere in that hierarchy. It’s how personal computers have worked for almost as long as we’ve had file systems on them. To those who are computer-savvy, or who grew up with computers, this makes complete sense. Of course they’re hierarchical - you have folders and subfolders to organize things, you have things separated by purpose, it makes for a powerful organizational tool.

But they’re the wrong way to do it. It makes sense for the engineers who built the systems - it’s easy and straightforward. But this idea comes from when computers were machines of science and war - not the personal computers we use today. The truth is, this way of doing things simply doesn’t make sense anymore.

I sense some of you are angry or confused with me. But hear me out.

I’ll start off with showing why and how this way of organizing files has failed, mostly with examples.

More Information About the Topic

File systems are the building blocks of files. It keeps track of what space is used and what isn’t, where files begin and end, and where everything is located. The fundamental ideas of file systems are fairly common, and work similarly no matter what operating system you’re on. Of course, there are lots of different implementations of this functionality. If you’re on Windows, you use NTFS. If you’re on a mac (or iOS device, for that matter), it runs on HFS+. If you’re on Linux, you most likely use Ext3 or Ext4.

For the record, NTFS and HFS+ are both outdated and lag behind their Linux counterparts. Apple is supposed to release a new file system this year, called APFS, that has some neat features, but in many ways it still falls short of the counterparts offered for Linux.

You need a file system, at least under the hood. Without it, you have no idea which physical parts of your hard drive are used and which ones aren’t. You don’t know when a file was last edited, how big it is, or where it is. It’s impossible to use a computer without one. But does it need to be exposed to the user? Maybe, but probably not as much as it is.

Also keep in mind that a lot of what I talk about here is already how iOS and Android work, at least to some extent, and I took a lot of inspiration from both their successes and shortcomings. While their methods still fall short of where they could be, I still believe that they’re a good milestone.

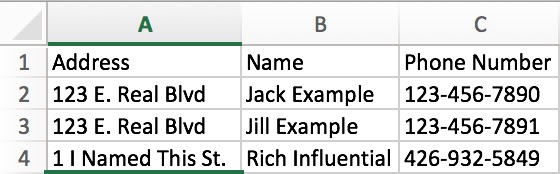

Finally, I’ll explain in simple terms what a database is. This is kind of tricky. Basically, it’s just a way of storing a lot of data, and keeping track of the relationships between data. For example, if we want to keep track of a list of houses, who lives in those houses, and what their names are, a database could do that. The easiest way to think about it is that a database is Basically a big Excel spreadsheet. You can put a ton of data in it. For each bit of information, you have a column (Address, Name, phone number in our example above). Each row is another entry, with another person. We can also filter or sort our entries by any of the columns too.

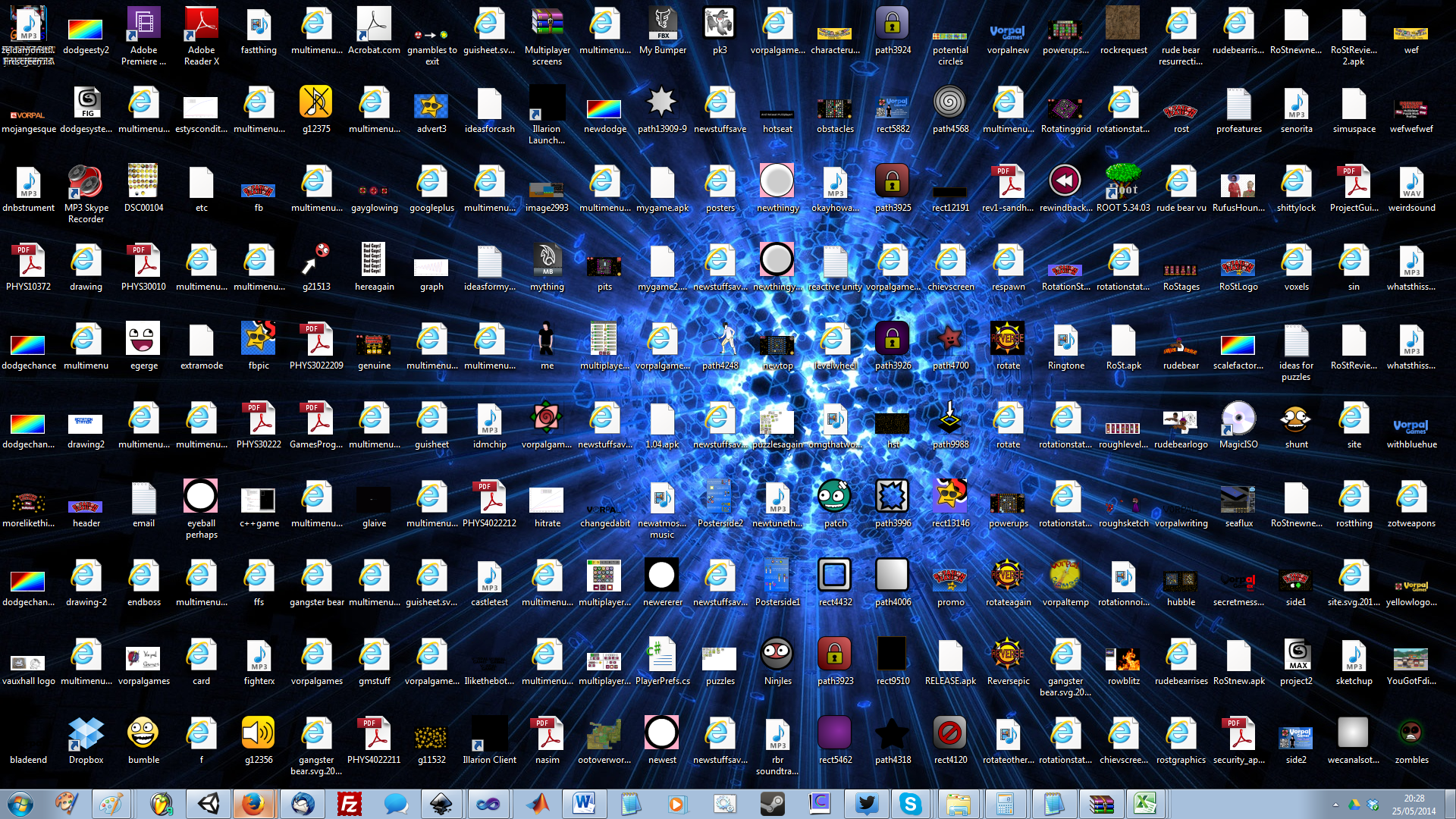

Example 1. The Desktop

We all know someone whose desktop looks like this. Hell, I’d barely blame you - the hierarchical structure of the file system basically encourages it. One of the basic principles of engineering a good user experience is this: minimize the number of clicks for a user to do what they want to do. Saving files to the desktop is the easiest way to do this. Want to open that word document you were working on? There it is. Don’t have to open up a file explorer, or remember where you saved it - it’s right there.

But I have a lot to say, so I’ll keep this brief. The point of a hierarchical file system is, supposedly, to keep things organized. This is the opposite of that. And why does this flourish? Because the file system encourages people to do this. It encourages people to be disorganized, in favor of convenience.

Example 2. Alfred and QuickSilver

Alfred and QuickSilver are mac apps, that allow you an easy to search your files and do some basic things. They were around before Apple revamped Spotlight to serve the same purpose. QuickSilver has been around for over 6 years, and it and Alfred were wildly popular in some circles, because of how much easier they made things. They solved the same problem that putting everything on the desktop solved - making files and applications easy to find and open.

Here’s how these work: Press cmd-space (or on Windows, the Windows-key) and start typing. Once you type enough of the app or file name, it pops up in search, and you hit enter. Bam, you opened a file with 0 clicks and a few keystrokes.

This makes it easier to stay organized, because opening a file is easy, regardless of how deep in the file system it is. But it’s another symptom of the problem - the fact that it was needed in the first place indicates a problem.

Example 3. Because I Always Follow the Rule of Three

Seriously, it’s built into me. I have to.

For this, you’ll need to understand what a symbolic link is. It’s basically a more powerful version of Windows shortcuts or Mac aliases, that works particularly well for folders. Basically, you tell the computer “Okay, when I say Documents/photos, just redirect me to my Photos folder”.

For this example, I’ll talk about how I organize my files. I’m obsessive with my file organization. I’ve got subfolder after subfolder, everything carefully named, everything in its proper place. No clutter. Basically the opposite of my home office. Then, I’ve got dozens of symlinks pointing to related folders (for example, my senior design code belongs both in the “MSOE” folder and the “Code” folder) so that everything is accessible from anywhere that makes sense. Then dozens more, carefully thought out, to offer good convenience while still minimizing clutter. Basically, I try hard to keep a clean and functional file system.

So let’s take just my Documents folder as an example. I have 0 files there, but 19 folders. 4 of those folders are hidden, because apps put stuff there and I couldn’t get rid of it. Another 4 of the folders are symbolic links, because either the OS does something that I have to work around, or it’s deeper in my file tree and I want shortcuts. One of those folders is google drive. For each subfolder in google drive, I have a symlink somewhere else pointing to it so I can make it accessible from a logical place. Some software wants to put folders in Documents, when it doesn’t belong there, so I make a workaround. Sometimes compatibility makes things act weird ways (like Google Drive) so I symlink my way around it. My point is, in order to organize my files logically, hierarchically, and accessibly, I need to use special commands and knowledge that the average user just doesn’t have. All to make the file system work nicely.

That is not the hallmark of a good system.

I believe that my way of organizing my file system among the most elegant, and one of the best I’ve seen. I’m really quite proud of it, but even then, I still feel it’s often quite ugly and hacky due to its constraints.

Technical Reasons

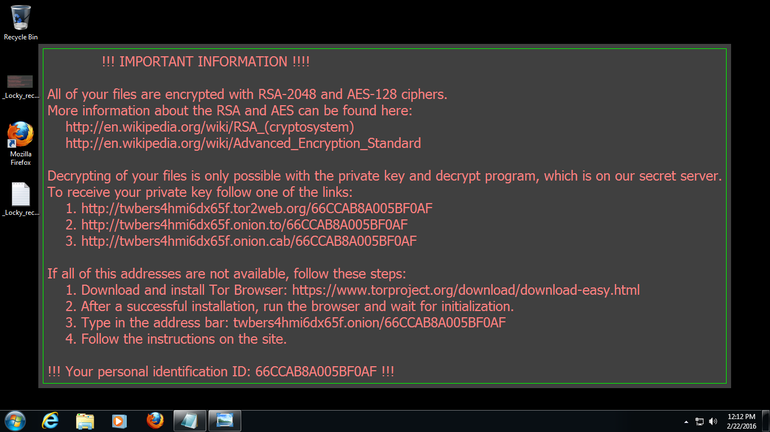

There are also technical reasons why this method of document management is flawed. The most obvious is viruses. Say you download some RansomWare. It starts encrypting all your documents, and BAM! you’ve lost everything. This only works because since the process is running in your name, the file system lets it access all of your files, without asking any questions. Say the RansomWare was disguised as a game - does it make sense for a game to open word documents? Absolutely not. But in the file system, they’re not distinguished in any way, so it can do it. That’s why you don’t really get RansomWare on iOS and Android devices - if they want to access your word documents, or your photos, or anything, they have to ask you for permission. Mobile devices already implement what I’m talking about here.

So while we’re talking about mobile devices, let’s bring up another point. On your phone, where are your photos located? Easy, in the Photos app. On your computer, where are your photos located? Probably all sorts of different places. In my opinion, this is why tablets and especially iOS devices are easier for the less tech-savvy crowd. Things aren’t organized hierarchically, but by application. Want to open a word document? Open word. A photo? Open Photos. A photoshop file? Open photoshop. The entire hierarchy is abstracted away from the user. It’s been proven that this is the safer and more intuitive way to do things.

From Wikipedia: “In software engineering and computer science, abstraction is a technique for arranging complexity of computer systems. It works by establishing a level of complexity on which a person interacts with the system, suppressing the more complex details below the current level.”

Why the Hierarchy Still Makes Sense

Don’t get me wrong, I don’t want to do away with it entirely. It makes sense for computers to be organized this way, and they have been for a long time. Computer scientists have figured out how to organize and work with it. The world’s servers are built on it, and it works great for that. It’s absolutely ideal for storing operating systems. My argument is only that, for users, the file system is an awful way to store documents and things.

On Linux and BSD systems, things are really cleanly organized in this hierarchy.

/bin is for binaries, /home is where users’ home folders are, /etc is

where settings live, and so on. This makes sense, for the purpose it serves,

and is actually a rather elegant solution. Again, my beef is with users’

documents.

Okay, Smart Guy, if the Old Way is Wrong, What Should we Do?

Thanks for asking. I’ll admit, this is a really hard problem, for various reasons. The most obvious is backwards-compatibility. File shares also pose a bit of a problem, but perhaps they can stay the way they are. There’s a multitude of things that would make compatibility here difficult, but this post is long as is.I’m just going to look at how I’d go about solving it on a single personal computer.

I’ll also say that people smarter than I have tried and failed to do this. Notably, the engineers at Apple attempted to do this with iCloud. It failed to catch on, and just doesn’t work very well in my opinion.

Here’s the problem with how Apple has been approaching these problems: They don’t want to fundamentally change the way they do things, they just want to sloppily tack new ideas onto the older software. The best example of this is their (soon to be obsoleted) file system, HFS+. HFS+ is the successor to HFS, and was basically just Apple tacking on some newer features to HFS through ugly workarounds. It’s somewhat infamous. When they tried to organize by app through their iCloud platform, they did something similar.

If we want to make a good solution to this, we need to be original. We need to be creative. We need to have some courage. While we work with half-measures and cop-outs to complete solutions, the system we create will be found wanting.

Personally, I think the correct answer to this is a database. We could build the database on top of the file system (this would actually make sense) but it would need to be ubiquitous. Why? This would allow extremely efficient searches of documents or apps by any criteria. Current file systems actually do something similar, but I want to take it to the next level.

Some of you may be wondering how I’d deal with projects. For example, in code, you have a whole folder full of files and assets, with lots of file types. I have some ideas about how to address this, namely by sandboxing the files in a single “project” file that’s actually a folder (kind of like how Apple handles .apps), but I won’t get into it here.

Next, we need a document manager. Actually, this would be pretty easy to write, even just on top of the file system. With the database, this would be incredibly powerful. If the operating system integrated it, it would be, in my opinion, the single best file manager in existence.

So let me walk you through how this would work. You open up the manager, and have a prompt in front of you. You type “Word”, and it shows you a list of all of your Microsoft Word files, organized by the last time you edited them. You’re looking for one about a short story, so you type “story”. Seven files pop up, and you press enter to open the one at the top. You don’t know what folder it’s in. You don’t care. But it’s easy to find, and it’s somewhere that makes sense.

Let’s get Technical

If you’re non-technical, you can skip this section. If you want to try anyway, you’re welcome to, but may find yourself needing to look a lot up.

Let’s say our database is relational, and built on top of the file system. This is basically how the indexing in file systems already works, but we can do better.

Each file has its own entry in the table. It has a path (this would have to be updated when the file is moved, but that’s pretty doable, at least in MacOS). The file has a path, an extension (.png), a file type (picture). Each file type has certain apps that are allowed to read and write it. For example, a picture would be readable by photo managers, office software, and loads of other stuff, and would be writable by things like photo managers and image editors. Only apps that are registered as a type’s reader (and approved by the user) are allowed to read that kind of file, and the same thing for writing. If a RansomWare app wants to encrypt all your documents, it’s gonna have to ask you first. Ideally apps have modular permissions (like how on iOS for any given app you can limit what device features it can access).

So there’s file-path is 1-1, file extension is many-1, file-type may be many-many (extensions may be registered to multiple apps. Stupid, but it happens). type-readapps is many-many, and type-writeapps is many-many. If you understand relational databases, this should make sense.

Obligatory “non-relational databases would be stupid for this” note: First, we know the exact structure of every table (aside from path size), and it’s very predictable. Even if we flesh it out and have a lot of tables, it’ll still be very simple. Second, this would be running on a single machine, there’s no reason for partition tolerance. Third, consistency and availability are both important here. Fourth, SQL is more mature and reliable. Fifth, a well-tuned SQL system will be much more quick and efficient. Sixth, stop trying to cop out of SQL just because it takes a bit more forethought.

The files are indexed by every major field one would search on. Name, create date, mod date, add date, read date, name, extension, file type, etc. I’d need to do a lot of analysis to figure out what compound indexes we’d want, but you get the idea (I hope).

The database, when presented with a document name, simply searches the files, which are of course, indexed by name. Easy and fast. Document type? Join the files with their types and filter on that. Extension? Even easier. App? Join app, read list, file type, and file, filtered by app. Easy.

We could even have our own “folder” system, based around tags. Tag it with “school” to go in the school folder. This also bypasses the problem of hierarchical file systems not being able to share a document between folders.

Some Credit to Mobile Operating Systems

Mobile operating systems had an opportunity to try doing things a new way, because they didn’t have to follow these aging paradigms. And I’ll give credit to them for trying something new, and something different. It’s still a young method to managing files, but I believe it’s maturing, and I believe that it more or less holds the keys to the future.

Closing

Now, I’m no user experience expert. But the traditional way is outdated, and worse, promotes bad practices. It’s time to rethink how we do things in an age where computers are consumer products, and not arcane machines operated by specialists. With the rise of touchscreen devices, we’re seeing lots of new ideas in this area, and I hope in the near future we’ll move on to a better system. Maybe you disagree with me. Actually, that’s pretty likely. But consider what I’ve said here, and keep an open mind. No system is perfect, but the simple fact is that the file system is from an age before the personal computer, and, in my opinion, we’re trying to put round pegs in square holes here.

Computer science has sped along at lightspeed over the last few decades. One of the downsides of that is that we’ve wound up with a lot of weird ways of doing things just because of backwards compatibility. As our field grows further, we need to find new and more efficient ways of doing things, and to fix our mistakes, as difficult as that may be.

Maybe you disagree with me on this point, and you may even be correct. But the above is what’s more important. We need fresh ideas, and open minds, about how to do things both old and new. The software engineering field is less than 100 years old (C is only 45 years old), and in a field this young, “it’s always been this way” just isn’t a good excuse.